Set Adrift On A Memory Bliss

This summer I was lucky enough to attend some amazing Bruce Springsteen concerts. In Milan, the San Siro arena was packed. No less than 70,000 people waiting the whole day for Bruce and the E Street Band to come out on stage.

Then the lights went down. Almost immediately, thousands of hands went up, and not (only) to applaud. They were holding softly glowing screens. Cameras and smartphones, not necessarily in this order, all straining to capture the show.

Although I’ll be the first to admit that I’m a social media addicted, I tend to limit myself to a snap or two at the beginning or end of a performance, trying to keep my focus on the show and not be distracted by Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

At this show, however, I noticed something different. With the notable exception of someone for whom, apparently, gig recording is a second job, people appeared to be trying to carve in digital form not the show itself, but the mood of the most memorable moments of the show.

Suddenly, I realized that instead of trying to obsessively document the night, Bruce’s fans were interested in capturing small snippets of the show to serve as a placebo in the future. The videos could augment that physical recollection of the night, rather than serve as a replacement for it.

This could be a sign that we are now in a sort of “memories overdose”: because of digital data and networks, we are in a situation where the amount of memories we can reasonably review has exceeded our capacity. Just take a look at YouTube statistics to see what I mean.

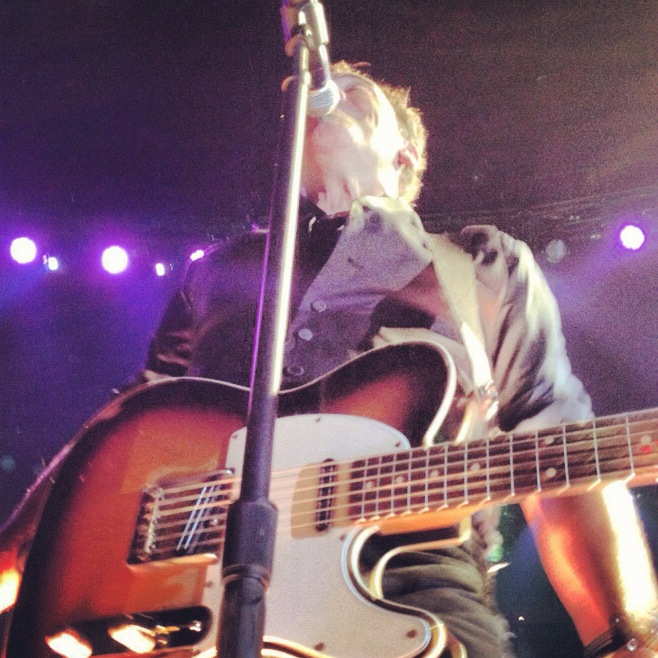

BTW, this is a pic taken in Milan from inside the pit. What a show… 😉